The term deckle edge refers to the distinctive, feathery edge of handmade paper. It occurs when the handmade paper is made. The name comes from the equipment used to make the paper, a mould and deckle. The mould is a wood frame covered with a special papermaking screen. The deckle is an open frame that is placed on top of the mould. The papermaker places the two pieces together and drags them through a vat of fibrous material floating in water, called the pulp, catching the fibers evenly on the screen. The deckle is removed and the sheet of paper is transferred from the mould to an absorbent surface called a felt for pressing the water out of the paper sheet.

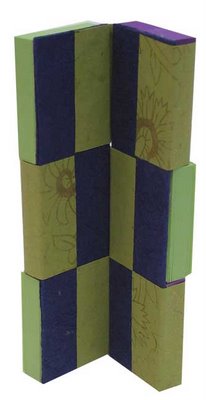

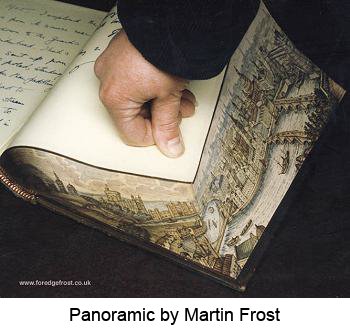

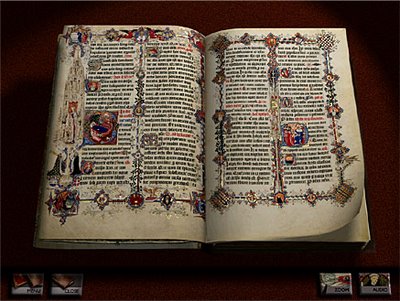

Handmade paper normally has four deckle edges and the edges are often quite dramatic while machine-made paper has two and are more subtle. Although early printers looked upon the deckle edge as a defect, and almost invariably trimmed most of it off before binding, in the latter part of the 19th century, it became the fashion to admire the deckle edge for its own sake, and to leave books printed on handmade paper untrimmed. Left in place, the deckle edge becomes a decorative, textured edging.

Handmade paper normally has four deckle edges and the edges are often quite dramatic while machine-made paper has two and are more subtle. Although early printers looked upon the deckle edge as a defect, and almost invariably trimmed most of it off before binding, in the latter part of the 19th century, it became the fashion to admire the deckle edge for its own sake, and to leave books printed on handmade paper untrimmed. Left in place, the deckle edge becomes a decorative, textured edging.Simulating a Deckle Edge. A true deckle edge can only be achieved during the paper making process. However, there are various ways to simulate the effect, some more effective than others.

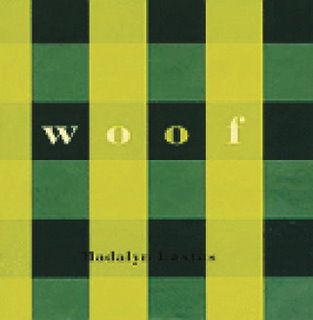

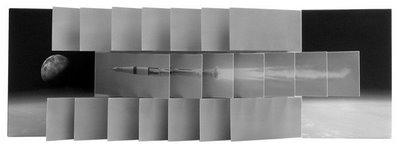

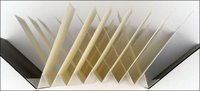

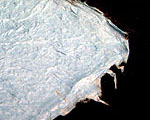

Tearing. The easiest way is to paint a line of clean water with a watercolor brush either freehand or held against a ruler, wait a while, then pull gently. Add more water or pull less gently depending on the strength and the grain of the paper and the effect desired. If you score the line first using a bone folder, then paint with water, the result is a finer edge.Photos of deckle edges (top): left: handmade paper; right: machine-made paper.

Rulers. Deckle patterned rulers are available against which the paper is torn. A wet tear will achieve a more feathery effect than a dry tear.

Scissors. Although the effect is decorative, deckle scissors, those with irregularly shaped cutting edges, create the least natural looking deckle edge.